By Marlize van Romburgh | Friday, May 9th, 2014

A Santa Barbara eye doctor and a drug that costs $2,000 per dose are at the center of the debate over how to control the spiraling cost of Medicare.

Dr. Robert Avery and his colleagues at California Retina Consultants are the top Medicare doctors in the Tri-Counties. They received $11.8 million from the program in 2012 for administering thousands of doses of Genentech’s Lucentis, a drug that treats blindness in the elderly but costs 40 times more than what many experts say is an equally effective and much-cheaper alternative made by the same company.

No one disputes that a new generation of drugs is delivering enormous benefits to an aging U.S. population. The cost of Lucentis, typically injected monthly, is one reason why ophthalmologists around the country are the largest recipients of Medicare payments, with eye care receiving $5.6 billion in 2012.

But the existence of the lower-cost Genentech drug, Avastin, has put Avery, a pioneering researcher, in the middle of a deep divide within the ophthalmology profession. Questions have arisen about drug-company rebates, the will of Congress to allow Medicare to negotiate reduced payments for high-cost drugs, Genentech’s refusal to seek approval for Avastin and the future viability of Medicare itself.

“In ophthalmology, you can plainly see this one single drug bankrupting the whole budget,” said Dr. J. Gregory Rosenthal, an ophthalmologist in Toledo, Ohio, who founded a group called Physicians for Clinical Responsibility to raise awareness of the high cost of Lucentis to taxpayers and patients.

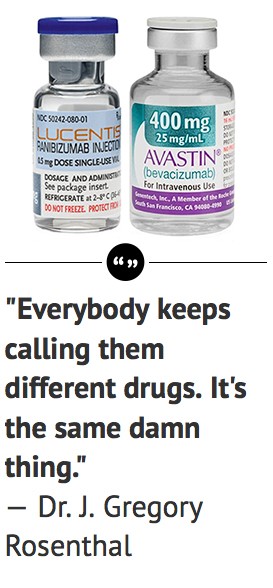

What is not in dispute is that the pharmaceutical firm Genentech pays rebates to doctors who use large amounts of Lucentis, which costs $2,000 per dose. It does not offer the rebates to physicians who use Avastin, a very similar Genentech drug that is approved as a cancer treatment but is also used “off label” by ophthalmologists who see similar benefits with a $50 price.

The drugs are derived from the same antibody. Both drugs are used by ophthalmologists to treat wet age-related macular degeneration, or wet AMD, the leading cause of blindness in the elderly, although only Lucentis is technically approved for that use. The Lucentis rebates, though entirely legal, serve as an incentive for doctors to use the more expensive medication.

“Rebate and discount programs are a common business practice across the industry,” Genentech said in a statement to the Business Times. “Our rebate and discount programs comply with all applicable laws and regulations and are transparent to the government through price reporting.”

The South San Francisco-based pharmaceutical firm has not pursued FDA approval for Avastin as a blindness treatment. But Avastin has been used for that purpose millions of times by doctors around the world, at a tiny fraction of the price of Lucentis.

“Everybody keeps calling them different drugs,” said Rosenthal. “It’s the same damn thing.”

$11.8 million reimbursement

Dr. Robert Avery, a pioneering researcher and one of the first ophthalmologists to use Avastin, now prefers Lucentis. (Business Times photo)

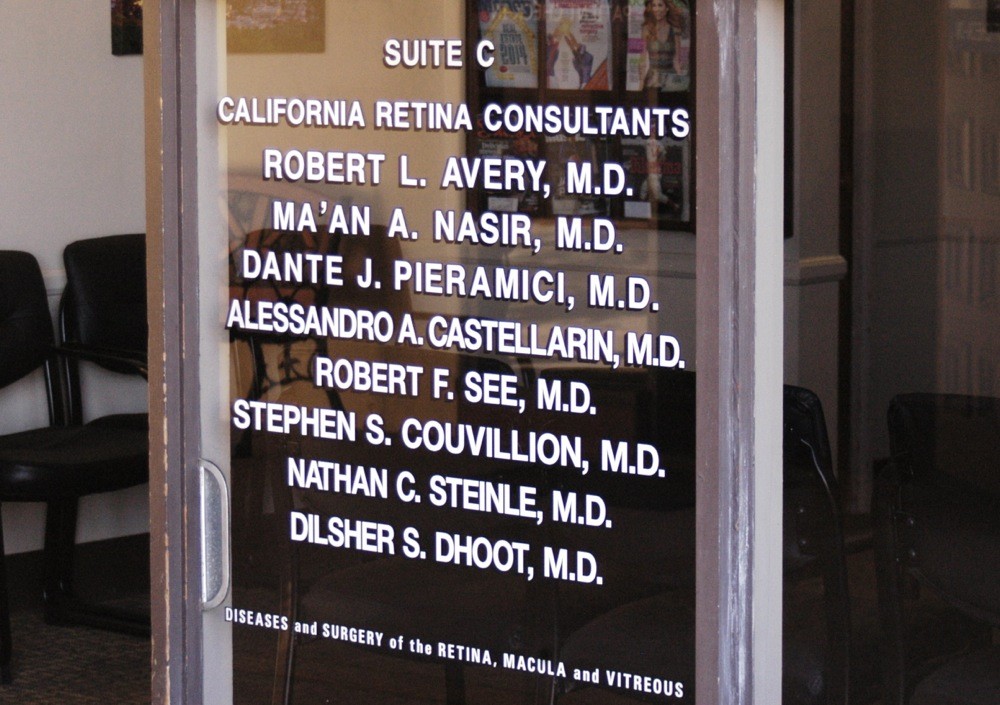

In 2012, six physicians at California Retina Consultants in Santa Barbara administered 7,348 doses of Lucentis to 1,358 patients for a total Medicare reimbursement of $11.8 million, according to data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Medicare reimbursed Avery $3.7 million in 2012 for 2,302 injections of Lucentis, compared with 267 injections of Avastin. Five other doctors at the Santa Barbara practice — Ma’an Nasir, Dante Pieramici, Alessandro Castellarin, Stephen Couvillion and Robert See — collectively billed Medicare $8 million for 5,046 injections of Lucentis.

As one of the top retina doctors in the country, Avery’s research has been published numerous times in medical journals. He’s quoted frequently as an expert in the treatment of AMD. After starting out as a solo practitioner in Santa Barbara, he has expanded California Retina Consultants to include 10 offices in the state.

Much of the group’s work is clinical research, and Avery said he’s proud of the numerous drug trials the group has done. In 2005, his practice became only the second in the country to use Avastin, originally used as a colon-cancer drug, as an eye medicine.

Now he is one of the top Lucentis users in the country and has a business relationship with Genentech. But his decision to use Lucentis has nothing to do with profits, he said.

“Foremost in our consideration is that the treatments we provide require frequent, sometimes monthly, needle injections directly into the eye. Lucentis requires fewer injections, and has a slightly lower risk of infection. For higher-risk patients, it may also have a lower risk of systemic side effects such as stroke,” Avery said in a statement to the Business Times sent through a public affairs consulting firm.

Avery said that he’s a paid consultant for several drug companies. He declined to say how much he has received in consulting and speaking fees and didn’t provide specifics about Lucentis rebates. “Treatments continue to improve,” he said in the statement, adding that he’s worked with Genentech, Eyetech, Regeneron, Allergan and others. “Because of my knowledge in this field, I’ve consulted for all of these companies, as well as others. I’ve also received grants to further study these agents.”

Equally effective

Six clinical studies comparing Avastin and Lucentis have found them to be equally effective.

The Comparison of AMD Treatments Trials, or CATT, studied 1,208 AMD patients receiving monthly doses. The trial was co-sponsored by the National Institutes of Health after Genentech refused to do a study comparing the two drugs. It was the first U.S. government-backed study looking at the so-called off-label effectiveness of a drug, in this case Avastin.

The CATT results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine in May 2011 and showed that the two drugs “had equivalent effects on visual acuity when administered according to the same schedule.”

The study found strokes and other serious side effects were more common with Avastin by about 5 percent. But the researchers said the increased risks could have been attributable to chance or different overall levels of health among the patients rather than differences between the drugs.

“Resolving this issue will require many more patients than were available for this study,” researchers said. The study noted that previous Avastin trials with cancer patients had not shown an elevated risk of severe side effects.

Avery said that while the chance of side effects is small with both drugs, the slightly higher risk associated with Avastin is why he choose Lucentis roughly 90 percent of the time.

“From all of my research and interpretation of the literature, Lucentis and Avastin are both good drugs, but there are significant differences between them,” he said in the statement. “Lucentis is FDA-approved for treating eye disease, while Avastin is FDA-approved for treating colon cancer, and must be divided into small doses for use in the eye. This process may induce a very small increased risk of serious eye infection. Lucentis also lasts longer than Avastin, and on average, requires fewer direct needle injections into the eye. We treat patients as individuals, and some patients respond better to one drug than another.”

The American Academy of Ophthalmology, a professional association of eye doctors, supports the use of both drugs. Most of its members prefer Avastin, with many citing the substantially lower cost to patients and taxpayers as a primary reason.

Medicare patients, who foot 20 percent of the cost of their own care under the program, pay $400 per dose of Lucentis versus $10 per dose of Avastin.

“We think that both agents, which appear to be equally efficacious, should be allowed to be used,” Dr. Michael Repka, the association’s director of governmental affairs, told the Business Times. “We think that decision should be between the patient and the physician.”

Billion-dollar difference

If all U.S. eye doctors used Avastin rather than Lucentis, taxpayers and Medicare patients would have saved $1.4 billion in 2010, according to a study of Medicare billing data conducted by the Department of Health and Human Services. On the other hand, if eye doctors switched solely to Lucentis, the Medicare bill would have jumped by $1.9 billion annually.

Medicare rules also allow doctors to charge a 6 percent commission above the cost of a drug. For Avastin, that commission comes to about $3 per dose. Lucentis earns $120 on each dose.

Genentech, which says its drug rebate program is essentially a high-volume discount, declined to answer questions about how much it pays doctors who use Lucentis or its relationship with Avery and his colleagues.

But several retina doctors who spoke with the Business Times said that for qualifying ophthalmologists, the Lucentis rebate is believed to be around $160,000 per doctor per year. That’s on top of the $120-per-dose commission that Medicare allows the physicians to collect, meaning that a doctor who uses large amounts of Lucentis can potentially reap significant benefits. Avery said that for his practice, AMD treatments are a break-even proposition.

Rosenthal, the Ohio doctor who questions the cost of Lucentis, said he believes drug-company rebates factor into medical decisions. “When you have the medical-industrial complex developing in such a way, companies can dictate how research is done and how physicians act,” he said.

Eyes on ophthalmology

California Retina Consultants in Santa Barbara. (Business Times photo)

Around the country, eye doctors consistently top the list of highest-paid Medicare doctors. Nearly 4,000 individual physicians each billed Medicare at least $1 million in 2012. Ophthalmology was the specialty that billed the highest total.

One reason is that eye disorders are among the most common afflictions to trouble Medicare patients, who are mostly people aged 65 or over. Eye doctors also have one of the highest overhead costs of any medical specialty, the American Academy of Ophthalmology said in a statement last month after Medicare reimbursement figures for 880,000 individual doctors around the country were released.

Those costs include not only staff, technology and equipment, but also “payments made to ophthalmologists for costly drugs used to treat eye diseases that are then passed through to drug manufacturers and suppliers,” the group said.

“Including those drug reimbursement dollars as part of a physician’s Medicare payment artificially inflates the amount paid to ophthalmologists,” the academy’s CEO, Dr. David Parke II, said in a statement.

Lucentis indisputably plays a large role in the high Medicare reimbursements for ophthalmology. Genentech recommends that doctors use Lucentis as often as monthly, meaning a treatment regimen for a single patient can cost $24,000 per year.

The courts and Congress have refused to allow Medicare to save money by pushing back against drug costs or by questioning doctors’ decisions, saying that doing so would amount to health-care rationing.

Miracle drugs

In less than a decade, Avastin and Lucentis have emerged as miracle cures for treating age-related macular degeneration, or AMD, a condition in which retina damage leads to vision loss.

While Genentech was still preparing Lucentis for commercialization, an ophthalmologist in Miami received permission from a patient suffering from AMD to inject the cancer drug Avastin into her eye.

The physician had realized that the two drugs were almost identical on a molecular level and didn’t want to wait for Lucentis to come out. The results of that first Avastin test were remarkable. With regular treatments, the patient’s vision was gradually restored.

Avery, the Santa Barbara ophthalmologist, quickly became an advocate for Avastin. “In 2005, before Lucentis was available, I helped pioneer the use of Avastin as California Retina Consultants was the second group in the world to use Avastin in the eye, and we published the first series of patients treated with it for macular degeneration,” he said in a statement. “Today, macular degeneration doesn’t cause nearly as much blindness.”

Genentech went on to pursue and receive FDA approval for Lucentis as an AMD treatment, then priced the new blockbuster drug at $2,000 per dose. Despite prodding by drug regulators to pursue on-label approval for Avastin as well, the company has refused.

“Rather than invest substantial years, resources and funds into the clinical development necessary to explore the safety and efficacy of Avastin in wet AMD, ultimately increasing its price when used in the eye, we believe it is in the best interest of patients to focus our efforts in ophthalmology — discovering and developing new potential medicines for other serious diseases of the eye,” Genentech said in an email to the Business Times. “Lucentis is already approved by the FDA to treat wet AMD, which addresses the previously unmet medical need.”

Still, Avastin is used in about 60 percent of AMD cases. “That’s in spite of the huge risks … the doctor takes” in using an off-label treatment, said Repka with the American Academy of Ophthalmology. “Most doctors are still using the less expensive drug, which ultimately benefits the patient and the taxpayer.”

Genentech’s South San Francisco headquarters. (Bloomberg News photo via Getty Images)

Print

Print Email

Email