By William Pesek

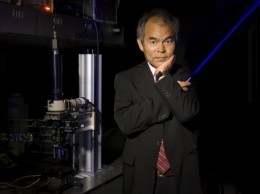

Japan’s media were exultant over a Nobel Prize in Physics award to three native sons. So it came as a shock when, rather than pop another champagne cork, co-honoree Shuji Nakamura poured cold water on the fete.

From his perch at the University of California at Santa Barbara, the 60-year-old scientist unloaded to a pack of giddy Japanese reporters about how Japan stymies the kind of innovation for which he was honored by the Nobel committee.

In Silicon Valley, where he moved in 1999, “everyone has a chance to dream the American dream,” he said. “Everyone has the chance if you work very hard.”

Not so in Japan, he said, where failures to internationalize, take risks and value employees by merit have led to years of stagnation in the fields of computers, smartphones, semiconductors and solar panels.

Oh, and as if to throw off Japanese conferenced in from Tokyo, Nakamura delivered his verdict in English. “It’s the main reason why American and Chinese producers took over these markets,” he said.

Nakamura told Kyodo News after his press conference, “If Japanese companies don’t reform drastically and implement English as their daily business language, the economy will only continue to contract.”

This month, as the current Diet session gets underway in Tokyo, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe faces an ideal opportunity to catalyze the kind of changes Nakamura is advocating.

Abe has pledged to lay out the specifics of his structural reform drive, which relies heavily on corporate tax cuts and reducing red tape. But he’s been quiet on one reform that truly would encourage the risk-taking culture Japan needs so badly: making sure employees get paid for their inventions.

Nakamura’s experience tells the story. Before heading to the U.S., where he’s now a citizen, Nakamura spent 20 years at Nichia Corp., a small lighting-product company on the southern island of Shikoku.

It was there that he made a major breakthrough in blue-LED technology, for which he shared the Nobel. In 1990, Nichia patented Nakamura’s advances, and the profits rolled in.

For his contribution, the company gave Nakamura a bonus of — get this — $180. In 2001, Nakamura sued over the rights to his discovery, which a Tokyo court ruled in 2004 could be worth, conservatively, $1 billion. In a settlement with the company, Nakamura got $8 million, a pittance by Western standards.

In a 2000 interview with Scientific American, Nakamura described how poorly equipped many Japanese labs were at a time when Apple and Microsoft were changing the world. Because his work initially garnered little revenue, he recalled, “gradually my company became mad at me.”

Today still, Japanese companies are reluctant to take risks with research and development or to compensate workers’ intellectual property. That reduces incentives to conjure up the next big thing, as the Sonys of Japan once did.

Technically, Japanese patent laws hold that in-house inventions belong to employees. In practice, though, that’s rarely the case: Executives use any number of loopholes to deprive workers of proper compensation for their ideas, or just assume a salaryman loyal to the company won’t demand his rights.

Nakamura’s legal victory really panicked the Japan Business Federation, or Keidanren, which then lobbied Tokyo to clarify that patent rights belong to companies, period.

Last year, Abe hinted he might do just that. But if he really wants to fuel innovation, Abe should do the opposite: change Japan’s patent law to ensure workers get a fair share of their contributions.

Why not spell out a 50-50 or 60-40 split between the visionary who dreams up the next big thing and the company that commercializes it? If a new generation of researchers like Nakamura were motivated by the almighty yen sign, Japan’s entire economy would benefit.

When Abe talks about Japan’s technological potential, he rarely misses a chance to mention robots. Yet far greater prosperity and economic growth would come from encouraging workers not to act like automatons. Abe should do so.

• William Pesek is a columnist for Bloomberg View. Reach him at wpesek@bloomberg.net

Print

Print Email

Email