Housing in Santa Barbara is a big, sticky subject made even more complex by wildfires, COVID-19, environmental concerns and a chronic lack of available units.

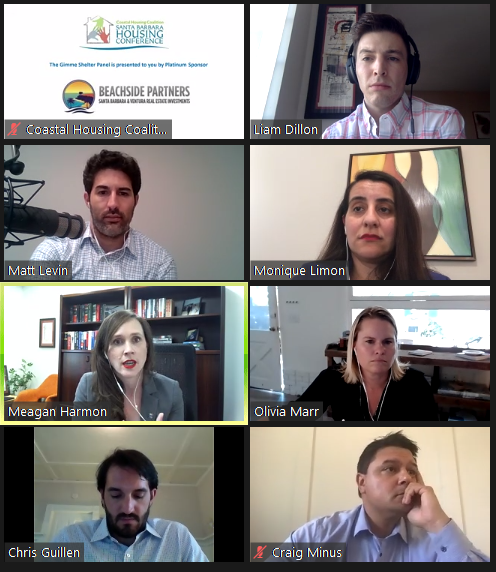

On Oct. 2, developers, architects, government and nonprofit leaders from all over the region got together, virtually, to highlight key issues and brainstorm a way forward, at the sixth annual Santa Barbara Housing Conference.

There were representatives from the city level, including Santa Barbara City Councilwoman Meagan Har-mon, as well as regional leaders like Assemblywoman Monique Limon, D-Santa Barbara.

Housing supply, and the lack thereof, was at the center of their remarks. Failing to build enough housing for a year or two is a problem, Limon said, while fail-ing to do so for decades on end creates a crisis.

“A small issue, unaddressed for decades, becomes a large issue, especially in regards to 2020,” she said.“What we were doing wasn’t working,” Harmon said. “To continue on and not build any new housing, like we haven’t done for 30 years, seems like doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.”

Both leaders acknowledged that care must be taken regarding where new housing is built. Limon spoke about evacuating from wildfires, and her concern about putting new housing in areas that had already been vulnerable or were affected by the Thomas Fire.

The conference featured panels, breakout rooms and a keynote speech from Dan Walters, a journalism with Cal Matters who has covered Sacramento for more than 40 years. In his keynote, Walters said there was a time when new housing and the population kept track with each other in California. But population growth quickly outpaced new housing, and housing dropped off during the Great Recession.

“Housing really never got back on track,” Walters said. “At least, not where it had been.”And, California has lost a lot of housing from natural disasters like wildfires.“We’re simply not building enough to barely, maybe, keep up with the deficit that occurred over the past decade,” Walters said.

Walters made the case that there is no way for the government to fund all of the housing the state needs in order to fill the backlog of affordable housing. Instead, it has to depend on private funding and construction—but it’s incredibly difficult for private industry to build housing in the state, he said, for reasons like zoning issues and environmental concerns.

The disasters of 2020 took some of the spotlight off the housing crisis, as the Legislature focused more on the pandemic, the economic downturn and the fires. But, Walters said, those other crises are having an effect on the housing crisis. “The wildfires are destroy-ing more housing that needs to be replaced. The pandemic is taking some pressure off of housing,” Walters said.

“It’s very difficult to determine how long these crises are going to last.” In a Q&A session after his speech, Walters suggested one way to address the housing crisis without further suburban sprawl is by repurposing existing structures and turning abandoned or otherwise empty buildings into new housing.

Other programs in the Housing Confer-ence examined more local aspects, including whether Santa Barbara might adopt more objective design standards and how the city might become less dependent on cars. One of the breakout groups after a panel discussed policies that make it harder for developers to build, like requirements to set potential third floors back a certain number of feet to avoid blocking others’ sunlight.

The conference also addressed the possibility people will lose their homes once the pandemic-related eviction bans expire, even with systems in place to allow renters to pay back the remaining balance over several months.

“I am worried we are going to have more homelessness as a result of COVID,” Limon said.

Harmon said she was also concerned about that possibility and wasn’t sure how local governments were going to get through the period after the eviction ban ends.

“This, along with the wildfires, keeps me up at night,” Harmon said

Print

Print Email

Email