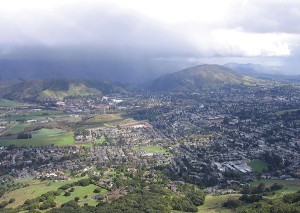

Although San Luis Obispo’s real estate prices are lower than in many other parts of the Tri-Counties, wages are lower too, and by a wider margin. (Creative Commons photo)

San Luis Obispo County has a problem with workforce housing. It doesn’t exist, and nobody wants to build it.

The struggle to manage the high cost of housing isn’t specific to SLO County. Even though housing is cheaper, in dollar terms, on the Central Coast than in other parts of the region, it’s actually less affordable because wages are lower there.

That’s why a coalition of industry groups and civic leaders in SLO County are pulling together a plan to make workforce housing easier and more attractive to developers.

The Economic Vitality Corp. of San Luis Obispo is bringing together six industry groups, with each tackling a different aspect of the deep-rooted issue. It’s part of a larger economic mission for the county, but many within the organization agree that housing is the cornerstone of the project.

Median home prices in SLO County hit the $460,000 mark in May, according to DataQuick Information Systems. But the median family income for the county is only about $72,300. This makes the county one of the 47 least affordable housing markets in the country, with most mortgages sapping roughly 41 percent of buyers monthly incomes, according to information from RealtyTrac.

Moreover, housing data for the county also suggests that rising home prices aren’t likely to taper anytime soon, making an already bad problem worse.

“A lot of groups have tried to attack the issue over time, but this particular [effort] seems to be gaining some momentum,” said Lenny Grant, principal with SLO-based RRM Design Group and co-chair of the building, design and construction industry cluster. “We’ve all known this is a problem for some time, but up until now there’s never really been a coordinated effort of so many different groups. For whatever reason the planets seem to be aligning, so we’ll see what’s going to happen.”

For now, the building cluster is taking the lead on the workforce housing project, with a primary focus on reducing county planning barriers and fees that diminish the financial feasibility for developers.

Draft recommendations from the building group are slated for review by the Board of Supervisors next month. Among the recommendations are: city and county plans, a fund that would be managed by the SLO County Housing Trust Fund and an employer-sponsored housing program. Also proposed are eliminating some homeowner association fees and outlining more flexible development criteria to allow for greater density on smaller parcels.

Grant said he hopes that incentives for development of workforce housing — which is currently less profitable than building market-rate single-family homes and condos — will level the playing field for potential projects. It’s obvious that developers gravitate toward higher profits, he added.

With development already strained by a lengthy entitlement process, the baked-in cost associated with projects makes workforce housing an even riskier proposition. The retirement of redevelopment districts, and the associated funds that could be used to subsidize workforce housing, was also a huge blow.

Additionally, the high fees associated with projects — up to $100,000 per unit, depending on the area — mean the economics just don’t work, Grant said.

“When you add land cost, cost of money, vertical building cost and risk cost, and that the banks are going to want a certain profit to lend on a project, the cards are really stacked against it … and that’s even if you a have developer willing to pursue it,” he said.

Aside from fees, there’s resistance from existing residents who are concerned about the environmental impacts of new development and their own property values.

Grant cited a project he worked on in Templeton that highlights some of the complex issues both developers and design groups are up against.

The property for the project was zoned by county planning officials for a density of 25 units per acre, even though most projects that were developed in the area previously barely gained approval with more than five units per acre. Grant knew the community would turn out in force to oppose the project.

So Grant and the developer decided to propose a 10- to 12-unit-per-acre mixed-density hybrid project. The application ended up kicking off a two-year battle with the county and residents, Grant said.

“It’s not a weird or extreme example, it straight up happens all the time,” he said. “On one hand, you have county planners pushing for high-density projects that are often influenced by the Urban Land Institute or American Land Institute. And then you have county officials who want the project, but communities that are almost always in complete opposition and are the same people who elected these officials.”

Broad-based effort

The EVC has enlisted other groups to help, including the San Luis Obispo Chamber of Commerce, the SLO County Board of Realtors and several large employers.

Companies realize that if they can’t attract and retain top talent, they’ll either suffer or have to pick up shop and move their headquarters to areas where a young dual-income family making between $100,000 and $120,000 per year can afford a nice home.

“[County planners] have seen their ideas go down in flames when we’ve brought projects forward, so they get it and they know there is a real problem,” Grant said. “That’s why I say the planets seem to really be aligning now, because we’re starting to get people to at least agree on what some of the problems are, what some of the solution might be and even what workforce housing really is.”

Dana Lilley, supervising planner for housing and economic development with the county, said the county is working on another wave of potential revisions to its regulations at the request of the building group.

“As land-use planners for the county, we are receptive to concerns and opportunities expressed by the development community,” he said. “While the lines of communication can always be improved, we believe that the county and the local development community are currently communicating pretty effectively, even when we are not in complete agreement.”

Workforce snapshot

The EVC building group will present the findings from its 2013 Workforce Housing Survey to the Board of Supervisors on July 15.

With about 467 responses from employees at area businesses, the building cluster officials say they have an accurate snapshot of what the workforce looks like. The survey includes details on commuting and what size homes area employees and employers are looking for.

With the survey, case studies and other supporting information in the works, Grant said the next step is developing an outreach plan. “There is still a lot of work to do,” he said.

Print

Print Email

Email